New IRS Guidance on Tax Treaties Provides Reassurance for Common US Cross-Border Investment Structures

In a general legal advice memorandum dated September 8, 2025, with a release date of September 19 (the “GLAM”),1 the Chief Counsel’s office of the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) addressed the application of the US branch profits tax (sometimes referred to as “BPT”) to income earned through non-US entities claiming treaty benefits on behalf of their owners, where the entity in question is fiscally transparent under the tax laws of the treaty partner, but has made an election to be or is otherwise treated as taxable as a corporation for US tax purposes (such entity, a “reverse foreign hybrid” or “RFH”).

Reverse foreign hybrids are a relatively common vehicle for structuring non-US, treaty-entitled investment into the United States, including over credit and yield strategies as well as private fund real estate strategies. The IRS has never before addressed the application of the branch profits tax to reverse foreign hybrids outside of limited guidance in certain treaties, and therefore the GLAM is important and reassuring in understanding how the IRS has developed its thinking with respect to these common structures. The facts of the GLAM are not squarely the same as the structures in the investment management area, however, and, as a result, caution should be taken in applying the conclusions to other fact patterns. Also important to note is that the GLAM cannot generally be relied on as binding guidance, and the GLAM itself suggests that further guidance in this area may be forthcoming and the GLAM would be superseded by any such guidance.

The US Taxation of Foreign Reverse Hybrids Generally

AN RFH is a non-US corporation for US federal income tax purposes.2 As such, an RFH is generally taxed on its US income in one of two ways. To the extent the non-US corporation earns US source income that is not connected with a “US trade or business,” it suffers a 30% gross basis tax, collected generally via withholding, that may be reduced or exempted by operation of a Code provision or the application of a treaty.

To the extent its US activities rise to the level of a “US trade or business,” an RFH's income is instead subject to net federal income tax. Whether a non-US corporation has a US trade or business is determined under common law, where the courts generally look to whether the activities of the non-US corporation or its agents within the United States are “continuous, considerable, and regular.”3 Income deemed associated with that US trade or business (such income, “effectively connected income” or “ECI”) is taxed at the same federal income tax rate as that of US corporations, currently 21%. In addition, non-US corporations engaged in a US trade or business generally suffer the BPT, which is a 30% tax on the “dividend equivalent amount” (“DEA”) of the non-US corporation.4 The BPT is intended to put a non-US corporation in a similar position when operating in branch form (the scenario where it is applicable), as it is earning US income through a US subsidiary. In this latter situation, a dividend withholding tax would otherwise be applicable to the US subsidiary (generally assessed at a 30% rate). The combined US federal income tax burden on the US trade or business of a non-US corporation can therefore be as high as 44.7%.

US Tax Treaties, In General

In US federal tax law, tax treaties exist alongside the US domestic law, and where they address a particular item of income or situation, taxpayers eligible to avail themselves of a treaty may be able to apply the treaty to achieve a better tax result.

To avail oneself of most US tax treaties (including all tax treaties entered into in the last 30 years), there is a requirement that the claimant be a tax resident in the treaty partner country (as residency is defined in the particular treaty), and in addition, the claimant must meet the requirements of a limitation on benefits (“LOB”) provision.

The General Application of Treaties to ECI and Branch Profits Tax

For income not associated with a US trade or business, the typical application of a treaty is to reduce the rate of withholding tax applied to the taxpayer. For situations involving a US trade or business, treaties generally provide three types of relief. First, where there is a US trade or business undertaken by a treaty claimant but the activity does not rise to the level of a “permanent establishment” under the terms of a particular treaty, the treaty may be able to be applied to exclude the income associated with the US trade or business from US taxation (a “No-PE Situation”). Second, where the activity does rise to the level of a permanent establishment, a treaty may also serve to restrict the amount of ECI associated with a US trade or business taxation to only that amount attributable to the permanent establishment (such income, generally termed the attributable “business profits”). Third, many treaties also provide for a lower rate of BPT as well.5

Treaty Fiscally Transparent Entity Provisions & Business Profits

Section 894(c) and the Regulations thereunder include rules for denying treaty benefits for certain payments made through an intermediate hybrid entity. Whether treaty access is permitted generally turns on whether the intermediate entity is fiscally transparent, as that concept is defined in the Section 894(c) Regulations, under the tax law of the treaty claimant. The Section 894(c) Regulations on fiscal transparency do not apply to business profits.

Most modern (i.e., post-1996) treaties contain language that directly addresses how to apply the treaty to income earned through intermediate entities (such an entity, where qualifying for look-through treatment entitling treaty access, a “fiscally transparent entity” or “FTE” and such treatyclause, a “fiscally transparent entity provision” or “FTE provision”). Broadly consistent with the concepts set forth in Section 894(c) and the Regulations thereunder, treaty FTE provisions generally provide that where income is earned by a treaty resident through an intermediate entity, the treaty can be applied to such income, provided that the treaty claimant [derives] the item of income arising through the intermediate entity for purposes of its own tax laws.

Unlike Section 894(c), treaty FTE provisions do not expressly exclude application to business profits. One Technical Explanation to a Protocol to a treaty addressed the application of FTE provisions to business profits.6 The IRS has not, however, previously addressed the application of FTE provisions to BPT suffered by RFHs.

As a general matter, applying a treaty to business profits earned through an FTE gives rise to two issues. First, there is the general question of whether the IRS would agree that in cases where the treaty does not directly address the applicability of its FTE provision to the item of income, that it should apply to such a situation. Second, and at issue in the GLAM, is the question of how to apply the treaty relief for the BPT to an FTE that is treated as a corporation for US federal income tax purposes (an RFH).

The Facts Analyzed in the GLAM

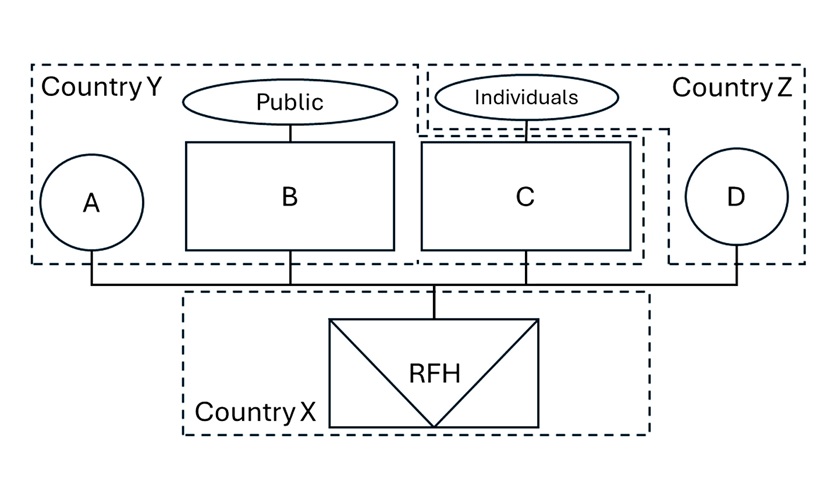

The GLAM addresses a fact pattern whereby a third-country entity is fiscally transparent under the tax laws of the country of formation (defined as “Country X”), as well as the tax laws of its owners. The entity is treated as a corporation for US federal income tax purposes (an “RFH”). There are three owners of the entity that are located in a treaty jurisdiction ( “Country Y” and the treaty, the “Country Y Treaty”), and one that is not (located in “Country Z”).

Owner “A” is an individual resident in Country Y. Owner “B” is a publicly traded corporate resident of Country Y. Owner “C” is a corporation tax resident in Country Y, owned by individuals resident in Country Z. Owner “D” is an individual tax resident in Country Z. A visual description is as follows:7

The facts provide that the RFH is either engaged in a US trade or business directly, or deemed to be engaged in a US trade or business as a result of the disposition of US real property, and that all of the ECI of the RFH is business profits attributable to a permanent establishment within the Country Y Treaty definition and, thus, all of its income is subject to tax and BPT, in the absence of the application of a treaty.8

The Country Y Treaty, generally, includes (i) a reduced rate of BPT; (ii) an FTE provision “worded consistently” with the 2016 US model treaty (the “2016 Model Treaty”); and (iii) the generally standard language that business profits of an enterprise of a resident of a Contracting State are taxable in the other Contracting State only if the enterprise carries on business in that other Contracting State through a permanent establishment to which those profits are attributable.

The Country Y Treaty includes an LOB provision that the GLAM concludes results in A and B qualifying for Country Y Treaty benefits generally, but C not qualifying, notwithstanding it is a tax resident in Country Y, because of its ownership by Country Z individuals.

GLAM Analysis

- General Observations

The GLAM first makes several general observations concerning the law related to RFHs, without citation:

- AN RFH is not eligible for treaty benefits itself; even if organised in a treaty country, given its fiscal transparency, it would in any event not be “liable to tax.”

- LOB is applied on an owner-by-owner basis to the RFH.

- If an RFH earns business profits that are not attributable to a PE (No-PE Income), the business profits “may qualify for an exemption” under the business profits article.

- The FTE provision does not change the identity or source of the income, or the RFH treatment, that otherwise applies.

- AN RFH that earns business profits must file a US tax return, and report any BPT, as well as any treaty-based reductions thereof.

- Application of FTE Provision to RFHs Earning Business Profits: In General

The GLAM then concludes that the FTE provision in the 2016 Model Treaty apples to business profits. While logical, this is the first time the IRS or Treasury has opined on this matter generally, outside of the specific guidance under the United States-Canada treaty.9 It notes that this conclusion comports with the plain language of the treaty, and observes that this reading is consistent with its purpose.10 The GLAM also cites recent developments in the OECD commentary that income earned through RFHs should generally be able to qualify for treaty access if the RFHs meet the FTE standard.

Applying this general holding, the GLAM next concludes that in the specific fact pattern set forth in the GLAM, the Country Y owners are considered to derive their share of the business profits of the RFH to the extent they are treated as earning the income under the laws of Country Y (i.e., the application of the FTE provision). In support of the per-owner-derived-by approach, the GLAM cites to the 2006 US model treaty technical explanation discussion of interest earned by a US person through a hybrid entity, as well as observing that this approach is consistent with the principles set forth in the Section 894(c) Regulations with respect to income not connected with a US trade or business.11

- Status of the RFH as a “Company”

Consistent with many US tax treaties, the Country Y Treaty BPT provision permits the application of BPT to entities that are a “company.” In observing that the application of the BPT is assigned under the treaty to the source state, the GLAM concludes that the relevant definition is that under US law, and the treaty does not change that treatment “in this context.”12 As such, the GLAM concludes that the RFH receives the business profits as a “company” under the treaty.

- Branch Profits Tax & 12-Month Rule

The Country Y Treaty provides for a 12-month residency requirement for the BPT entitlement to apply. This is determined under the treaty on the date on which the DEA is determined. The GLAM concludes that in applying this provision, the relevant date for testing is the last day of the tax year of the RFH, because that is the date under US federal income tax law that the DEA becomes fixed.13

- Branch Profits Tax & Individual Treaty Owners of the RFE

Some taxpayers have attempted to take a position that the BPT does not apply to an RFH earning business profits to the extent the owner of the RFH is an eligible treaty claimant that is taxed as an individual (BPT does not apply to individuals). These taxpayers have sought to argue that the RFH is not subject to BPT because the FTE provision applies on a look-through basis, and looking through, BPT is inapplicable to an individual taxpayer. Other taxpayers have been hesitant to apply any treaty-based reduction to BPT through an RFH on the amount of the DEA attributable to an individual owner, due to the concern that the IRS may be able to assert that there is no treaty resident “company” that can claim the BPT reduction.

While concluding that the treaty applies to the business profits earned by the RFH (on a per-owner-derived-basis), the GLAM rejects the notion that BPT can be avoided by looking to the US domestic law status of the owners. This is because, the GLAM concludes, the “relevant taxpayer” is the RFH under US federal income tax law, and “[i]nterpreting the interaction of the FTE and BPT provisions in this manner gives proper effect to both provisions while maintaining the source State’s right to treat the entity as the taxpayer under its domestic law.”

Citing to both the OECD commentary and the language of the 2016 Model Treaty in support of this position, the GLAM concludes that while the FTE provision generally adopts a look-through approach, this allows for exceptions where necessitated by “the nature of the taxpayer.” This modification to the look-through approach is required in this instance, the GLAM concludes, to give effect to the treatment of the RFH as a corporation under US federal income tax law, as well as the appropriate rate of BPT under the treaty.

Therefore, in analyzing the RFH’s BPT attributable to Owner A of Country Y (an individual), the GLAM concludes that such amount is subject to BPT at the reduced rate under the treaty. In other words, the BPT treaty rates enjoyed by the RFH derive from Owner A’s treaty status, rather than from Owner A’s tax classification for US purposes.

Mayer Brown Observations

- In General

The conclusions set forth in the GLAM with regards to the per-owner application of relief under the treaty for business profits derived through an RFH are generally consistent with market practice and should provide confirmation for taxpayers in such structures. Several points should, however, be taken into account:

- Some taxpayers have taken the position, as noted above, that individual owners of an RFH should not suffer BPT at all, because the FTE provision applies a look-through concept, and individuals do not suffer BPT under US federal income tax law. Others have applied full BPT for the portion of the DEA attributable to individuals through an RFH, on the theory that there is no treaty resident “company” that can claim the reduced BPT. The GLAM refutes both positions, and takes the position the individual’s DEA portion can receive the reduced treaty BPT rate. Taxpayers taking the position that they are exempt from BPT, furthermore, should now be on notice that the IRS would seemingly disagree with any such assertion when taken on a tax return. In addition, the GLAM puts taxpayers on notice that forthcoming guidance is anticipated, which may further address this particular point.

- The Country Y Treaty analyzed in the GLAM follows the 2016 Model Treaty, particularly Article 10, in applying a uniform rate of BPT reduction. The GLAM fact pattern, however, brings into question a different, common, real-life scenario, in that in some treaties a publicly traded corporation (and often certain other entities) may avail itself of a lower BPT rate than the general treaty BPT rate or a BPT exemption.15 The GLAM fact pattern includes Owner B, which is a publicly traded corporation, but does not address the application of a treaty that potentially provides for a different rate of BPT in such a case. There is nothing in the GLAM that would appear to suggest that such a special reduced rate or exemption should not be available; indeed, the general reasoning set forth in the GLAM (in particular the conclusion that the DEA is deemed earned by each owner) could suggest a favorable conclusion that the lower rate or exemption could apply. It seems odd that the GLAM included such a publicly traded corporation as an owner, but limited the facts to the 2016 Model Treaty clause that did not address different BPT rates.

- Likewise, it seems odd that the GLAM would include as a fact pattern Owner C, which is a Country Y resident that does not meet the LOB and does not meet an active trade or business test. The GLAM makes an assumption that the active trade or business test is not applicable to these facts, which is unfortunate, as it would have been helpful to see the IRS’s analysis of the application of treaty BPT rate relief where Owner C had an active trade or business, and whether the IRS feels there are any additional concerns in this fact pattern.

- The GLAM does not address the scenario where an RFH earns the business profits itself through a US entity that is not fiscally transparent in the RFH owner’s jurisdiction (e.g., through a US limited liability company). Some taxpayers have asserted that because the BPT is assessed under US federal income tax law on the RFH, the FTE provision should not prevent the application of the treaty to reduce BPT in such an instance, because the tax arising is at the level of the RFH. This issue is not addressed in the GLAM, but may be subject to forthcoming guidance.

- In analyzing the application of the 12-month residency test under the Country Y/2016 Model Treaty, the GLAM observes that the owners of the RFH must meet “the more than twelve month period” on the close of the RFH’s tax year. The 2016 Model Treaty provides for a “twelve-month period,” not a “more than twelve month period,” and it is unclear where the GLAM obtains this reference. If the relevant clause is to be interpreted as “more than” twelve months, there could be scenarios where no owner would meet the required test, presumably, in the first year of operation. Without further references, we think this may be an error in the GLAM.

- The GLAM observes the Country Y/2016 Model Treaty FTE provision requires that the treaty claimant must be “subject to tax” on the item of income through the FTE for it to qualify under the FTE provision. The 2016 Model Treaty, however, includes no such requirement. It provides that treaty relief is available through an FTE, “but only to the extent that the item is treated for purposes of the taxation laws of such Contracting State as the income, profit or gain of a resident” (emphasis added).16 This is an important distinction for many taxpayers, including many government entities, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, and entities with a special tax exemption, that may not be “subject to tax” in their country but are nevertheless eligible for treaty benefits generally (many treaties, for example, specifically provide for residency and LOB status for such entities, notwithstanding they may not be “subject to tax”). Where the applicable treaty provides treaty availability for such entities, there should be no less relief available under the FTE provision (a result consistent with its wording). We cannot surmise that the IRS actually meant to apply a higher “subject to tax” standard in such a case, which would not be supported by the plain meaning or purpose of the treaties generally, or the FTE provision specifically.

- Application to Common Market Structures & Participants

The scenario addressed by the GLAM is somewhat unusual, in that it finds several individuals investing alongside a public corporation into an RFH, a situation we would observe as highly atypical. The GLAM does, however, have implications for several more common investment scenarios.

- Structuring inbound US investment through pooled or single owner RFHs has become a popular structure for non-US investors seeking exposure to or investment in US assets that generate business profits. This is because the RFH structure provides treaty access, while also enabling investors to avoid the requirement to file a US tax return. This GLAM will provide helpful reassurance to the market that the IRS understands these structures and interprets the application of the FTE provision in a manner that permits these structures to maintain this efficient balance of treaty access and administrability.

- The GLAM makes the observation, as noted above, that in a No-PE Situation an RFH should be able to take the position it is not subject to tax on its business profits. This is a critical conclusion, as many inbound lending structures use RFHs while taking the position that they do not give rise to a permanent establishment. While unfortunately the GLAM does not spend time analyzing this particular situation (and makes this legal conclusion without citation), it is reassuring that the IRS has acknowledged this fact pattern and concluded that it should likely be treated consistently with how the market has generally concluded it should apply.

- Some investment structures have RFHs that have US investors alongside treaty-entitled investors (for example, in a situation where a US trade or business is not anticipated, or may not be material). If these structures do have business profits, the market generally takes the position that treaty BPT relief is available on the portion of the business profits allocable to those other, treaty eligible RFH owners, and is not impacted by the presence of the US owners. The analysis set forth in the GLAM, while not directly addressing this point regarding US co-owners, would appear to confirm a conclusion that there is no reason to regard the treatment of the RFH as different where a DEA is allocable to a US owner than other non-treaty owners of an RFH, as illustrated by the analysis of Owners C and D in the GLAM.

- Non-US pension funds are significant investors in the United States, and many have made their investments in the United States. through RFH structures. Some of these pension funds are taxed as individuals under the Code.17 As noted above, the GLAM would appear to suggest that the IRS would disagree with an assertion by such pension funds that their BPT should be eliminated, because of their status as individuals for US federal income tax purposes. However, in the case (as in many treaties) that the treaty reserves a 5% BPT rate for pension entities, the observation above regarding special reduced BPT rates would be applicable. Therefore, pension entities (regardless of their status as trusts or corporations) eligible for the reduced 5% BPT rate in treaties should find this guidance helpful in assessing their BPT exposure through RFHs.

1 AM 2025-002. A “General Legal Advice Memorandum” does not constitute binding guidance on the IRS or a taxpayer.

2 Reverse foreign hybrids raise complicated US state tax issues in addition to the issues addressed herein regarding US federal income tax. These US state tax issues are outside the scope of this discussion.

3 See De Amodio v. Comm’r, 34 T.C. 894 (1960), aff’d on other grounds, 299 F.2d 623 (3d Cir. 1962); Pinchot v. Comm’r, 113 F.2d 718 (2d. Cir. 1940); Lewenhaupt v. Comm’r, 20 T.C. 151 (1953), aff’d, 221 F.2d 227 (9th Cir. 1995). A US trade or business of a partnership through which a non-US corporation invests is generally attributed to the non-US corporation. Section 875(1). All Section references are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, and all references to Regulations are to Title 26 of the CFR.

4 The branch profits tax applies only to non-US corporations and not to persons taxed as individuals. See Section 884(a). The DEA is the non-US corporation’s effectively connected earnings and profits, adjusted for certain increases and decreases in US net equity of the non-US corporation. US net equity, in turn, is the excess of the basis of the assets over the liabilities, in each case, connected with the non-US corporation’s US trade or business.

5 Section 884 was enacted in 1986, and certain treaties in force prior to the introduction of the branch profits tax were deemed to not permit the application of BPT. The treaties that are still in force that exempt BPT are those with the People’s Republic of China, Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Jamaica, Morocco, Norway, Pakistan, the Philippines, and South Korea,. See Regulations section 1.884-1(g)(3). While the treaty with Australia currently in force predates the implementation of the branch profits tax, the BPT may still apply under the Australian treaty at a reduced rate of 15%. See Regulations section 1.884-1(g)(4)(B).

6 See the Technical Explanation to the 2007 Protocol to the United States-Canada Income Tax Convention, at Art. 2 para 6.

7 RFH is depicted as per custom as a fiscally transparent entity (a partnership) that is treated for US federal income tax purposes as a corporation; an RFH is generally depicted as an upside-down triangle within a box, to distinguish it from a “hybrid entity” that is a non-US opaque entity treated as fiscally transparent for US federal income tax purposes, that is customarily depicted as a triangle inside a box.

8 The GLAM makes what appears to be a simplifying assumption by stating that the RFH distributes all of its income to its owners and makes no reinvestment in its US business, with the result that the DEA is generally equal to its net income.

10 For support for this conclusion, the GLAM cites the 2006 Model Treaty Technical Explanation, which explains that the FTE provision there (substantially similar to the 2016 Model) was meant to pertain to all types of income covered by “the substantive rules of Articles 6 through 21”, and Article 7, business profits, is within that referenced range. See Technical Explanation to the 2006 US Model Tax Treaty, Art. 1 para. 6.

11 In observing that the Section 894(c) Regulations reserve on this exact question of business profits earned through an FTE, the GLAM notes that those Regulations predated the FTE provision contained in modern treaties (as well as the 2006 model treaty and the 2016 Model Treaty discussed in the GLAM), and as discussed above, the GLAM concludes that the FTE provisions are broader in application than just withholding taxes. The GLAM further observes that the Section 894(c) Regulations preamble contains a statement that the approach taken in the Regulations is meant to be consistent with the approach taken in the 1999 OECD publication, the “Application of the OECD Model Tax Convention to Partnerships,” and that report did not limit its approach to withholdable income (the “OECD Report”).

14 Citing OECD Report, at R(15)-33.

15 See, e.g., the 2001 United States-United Kingdom Income Tax Convention, Art. 10(7)(b).