The FTC’s Proposed HSR Changes: What They Mean for Dealmakers

The sweeping revisions proposed by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to the premerger Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (HSR) notification rules would be the most significant change in the 45-year history of the program.1

If the revisions are implemented (which we do not expect to occur prior to the end of the year), parties making filings will need to:

- Provide significantly more data on many issues (including data on their employees) and troves of internal strategic plans, reports, and deal-related documents;

- Write detailed narratives about the transaction (including its rationale and synergies), the parties to the deal, and the markets in which they operate;

- Dedicate significant additional resources to preparing the required HSR filing; and

- Lengthen their expected timeframe to obtain merger clearance.

All of this serves to increase the complexity, risk and uncertainty of the merger review process.

Of course, while these changes make the premerger process more burdensome, they do not alter substantive antitrust doctrine. For the government to block a deal, it still must prove in court that a merger or acquisition is likely to result in a substantial lessening of competition.

We provide below a summary of the proposal, the FTC’s rationale for it, and considerations for what the new rules, once implemented, will mean for deal teams. The details of the proposal may change as the rule-making process unfolds (including an opportunity for public comment),2 but the Administration is likely to move forward with the key provisions.

THE SCOPE OF THE PROPOSED RULES

The proposed rules affect all aspects of the HSR initial notification process. While the proposal does not and cannot alter the statutory mandates for the types of transactions that must be reported (i.e., those subject to certain size of person and size of transaction tests) or the applicable waiting periods (i.e., typically 30 days for the initial review), practically everything else is fair game.

The proposal affects the HSR Form itself, the information that must be submitted, and the process for doing so. The details are daunting (40 single-spaced, small-font Federal Register pages), and, once implemented, the proposed rules will cause a sea change in the traditional HSR premerger process. Moreover, given the subjectivity of many of the new requirements, it will likely take years of give-and-take between parties and the FTC Premerger Notification Office for there to be a practical understanding of the true metes and bounds of what the new rules do and do not require.

The most salient features of the proposal would require merging parties to provide:

- Details about the structure of the transaction, its business rationale, and the entities involved in it, including significant information on minority and private equity investors and “entities or individuals that may have material influence on the management or operations” of the acquirer, such as certain creditors, board observers, and management service providers;

- Narrative descriptions of the parties’ products and services, the markets in which they are offered, and up-front assessments of “horizontal” overlaps and other interactions between the parties (which the FTC identifies as “non-horizontal business relationships”), such as supply agreements;

- A vastly expanded set of the “Item 4(c) and (d)” deal-related documents covering competition topics that must be submitted, including all draft documents (instead of just the final version) and documents prepared by or for the supervisory deal team leads (regardless of whether the leads are officers or directors of the company), as well as ordinary-course strategic plans and reports regardless of whether they were created in connection with the deal;

- Details regarding prior acquisitions, especially any non-reportable deals;

- Names and contact information of officers and board members as well as other companies for which those individuals have served in comparable positions, as well as names of prospective officers and directors;

- Disclosure of information that screens for labor market issues by classifying employees based on certain job categories and geographic market information (“commuting zones” in which both parties employ workers in such categories), as well as information on any past worker and workplace safety violations;

- Identification of all communications systems or messaging applications on any device that can be used to store or transmit information or documents relating to business operations;

- Certain foreign subsidy information, as required by Congress; and

- Certification under penalty of perjury that “the necessary steps to prevent the destruction of documents and information related to the proposed transaction before the expiration of any waiting period” were taken. (In other words, the FTC deems all HSR-reportable transactions to require a litigation hold.)

The changes will require significant additional work, with the FTC predicting that conformity to the proposed rules would result in approximately 12 to 222 additional hours per filing. Such predictions appear conservative. Moreover, these changes apply to all HSR filings, not just ones involving competitors.

WHY ARE THESE CHANGES NEEDED?

The FTC states that the new disclosure requirements are to “enable the Agencies [the FTC and the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice] to more effectively and efficiently screen transactions for potential competition issues within the initial waiting period.”3 The HSR Act and its implementing rules require the parties to certain mergers and acquisitions to submit premerger notifications to the Agencies and to wait a specified period (typically 30 days) before consummating their transaction. At the end of the initial waiting period, the parties can close unless one of the Agencies issues a Request for Additional Information (Second Request), thereby triggering an in-depth review. The parties can also “pull-and-refile” at the end of the initial waiting period to provide the Agencies an additional 30-day waiting period prior to the decision on whether to issue a Second Request.

The FTC states that the rule changes “seek to fill key gaps that our staff most routinely encounter, such as inadequate information about deal rationale or the details of how a particular investment vehicle is structured.”4 Of course, the agencies can obtain such information under the current rules by asking the parties to provide it voluntarily during the initial waiting period. Most parties work to expeditiously answer any questions an Agency may have and to respond to requests for information.5 The Agencies can also access public information about the companies, their products, and the transaction. And the Agencies can reach out to third parties to gain a better understanding of the marketplace, as well as receive complaints from those who are concerned about the deal. In the highly unlikely event that an Agency misses a competitive issue raised by a transaction and fails to issue a Second Request, an Agency still has the ability to investigate and challenge a deal, even after it closes.

To be sure, the proposed rules will provide more up-front information for Agency staff to consider, but is the extra work that will now be required for all HSR-reportable transactions worth the cost to the parties, as well as the time for agency staff to review this information for each filing? The FTC notes that 45% of HSR filings check the box for an “overlap” according to NAICS code revenue, thereby implying a competitive relationship between the parties in nearly half of all HSR filings.

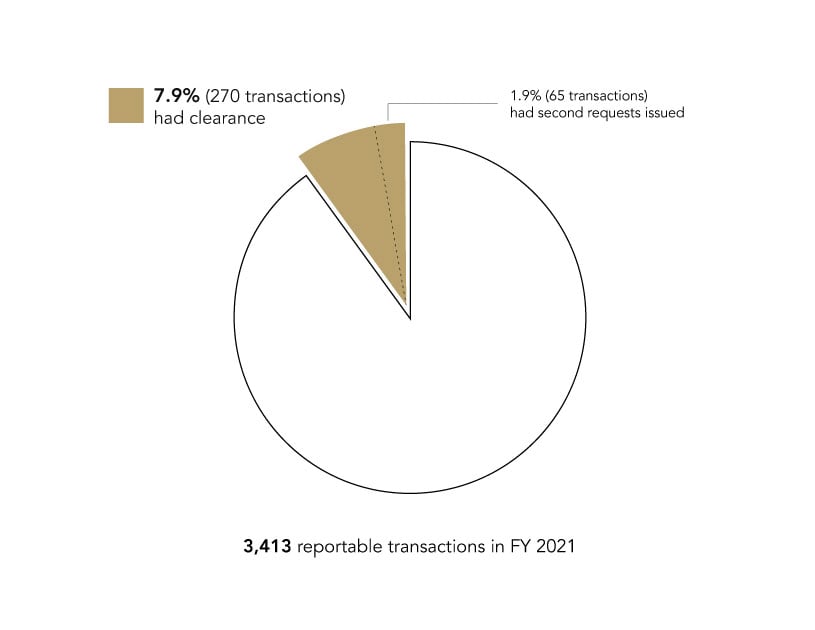

But NAICS codes are notoriously imprecise. The percentage of HSR filings raising competition issues worthy of the Agencies’ investigative attention is most likely much lower than 45%. For example, the Agencies submit “Annual Competition Reports” to Congress with detailed data on HSR filings.6 Fiscal year 2021 (October 1, 2020, through September 30, 2021) was a high-water mark for HSR-reportable transactions, with HSRs for 3,413 transactions filed that year. Of those, the FTC or the Antitrust Division sought “clearance”—stating an interest in looking into a specific deal7—for 270 (7.9%) transactions; and the Agencies ultimately issued 65 Second Requests, for only 1.9% of all transactions.8

In other words, the Agencies had no interest in the overwhelming number of reported transactions (3,143 of 3,413, or 92% of the FY 2021 total). It is safe to assume that these transactions therefore raised no competition issues. The figures for other years are comparable.

Yet, under the new rules, the parties making filings in those 3,143 transactions would have to incur the significant costs to provide the newly requested detailed information.

WHO WILL BE IMPACTED?

All entities involved in HSR-reportable transactions will be impacted. The proposed rules are generally applicable and cover all reportable transactions. There is no particular industry focus, other than a mention by the FTC about the importance of obtaining information about prior non-reportable deals in the tech industry.

The FTC asserts that the impact may be less than what it first appears to be because “[m]any of the updates in the proposal are consistent with data already collected by antitrust authorities around the world.”9 Indeed, in a sense, the proposed rules basically transform the United States from a notice-filing jurisdiction into one with requirements more like what is typical in the European Union10 and other comparable merger regimes, including a detailed transaction description; the economic deal rationale; narratives describing all horizontal overlaps, vertical relationships and other relationships (such as conglomerate effects) arising from the notified transaction; data on markets affected by the transaction; an analysis of the effects of the transaction on competition; efficiencies (where applicable); and relevant internal documents. So, for transactions requiring such foreign filings, the parties may have some synergies. And firms that frequently file HSRs will surely develop templates and protocols to be able to efficiently track the additional data required by the new rules.

But reliance on foreign filings to minimize the impact of the proposed rules misses two important qualifications:

First, only a limited number of HSR-reportable transactions also require foreign filings. Rather, most HSRs reflect transactions between US companies in which the HSR is the only pre-merger filing that must be made. While we are not aware of statistics providing such data, the current HSR Form asks for voluntary disclosure of the foreign filings being made for the reported transaction. A summary of the number of US HSRs that were subject to multi-jurisdictional filings would be helpful to test the degree of the expected synergies.

Second, the proposed rules go much farther in certain respects than what is required by other countries at the initial stages of notification. For example, the proposed rules:

a) Mandate the up-front production of an inordinate number of documents that simply are not at issue in initial foreign filings.

b) Make an unprecedented requirement for labor market information (such as employee classifications, geographic market information for each employee classification, commuting zones, and worker and workplace safety information), which is absent from the competition assessment by the European Commission and most other competition authorities worldwide. (Rather, review of this type of granular employee information is more common in regimes where public interest considerations are balanced with competition considerations during the substantive assessment.11The new requirements under the proposed rules, however, will apply to all US HSR-reportable transactions even though there is a dearth of US merger caselaw on what constitutes cognizable merger-related harm with respect to employees.

In short, the impact of the new rules will be far-reaching and extensive.

From the inception of the EU merger control regime, a practice developed of agreeing waivers with the European Commission from the strict requirements of the notification form, and over time a short form procedure was introduced for notifiable transactions that were unlikely to give rise to substantive issues. It is to be hoped that similar, or other, mechanisms might be adopted in the HSR process to reduce the burden on the parties to notifiable transactions so far as possible, consistent with the objectives of the new regime.

WHAT WILL THE NEW RULES MEAN FOR MY DEAL?

The short answer is that the proposed rules will make the preparation and filing of HSRs take longer and cost more, thereby introducing more uncertainty and risk into the deal process.

Timing: Under current practice, most HSR forms are prepared and filed between 5-10 business days following deal signing. (Parties can also file on a letter of intent before the deal is signed, but the proposed rules place further burdens on that practice as well.12) Under the proposed rules, parties will need more time to compile the requested information, draft narrative responses, and otherwise complete the filing. Each deal is unique, but the time for such tasks could easily add weeks to the timeline.

But there is an even further risk: As previously stated, the HSR statute provides that the initial waiting period is 30 days; the FTC cannot change that requirement. However, could the FTC “bounce” filings that they deem deficient for failure to meet the subjective requirements of the new rules, such as overlap descriptions and deal rationale? If so, it is foreseeable that the US will turn into more of an EU-like system where the parties engage in significant pre-filing “consultations” with the FTC, providing iterative drafts of the filing until the agency is satisfied. There would be little predictability for when the thirty-day clock would begin to run.

Costs: The new rules will significantly increase the costs associated with compiling the required information, producing the requested documents and drafting the filing. But the costs are much more than monetary. The rules will place an increased burden on the deal team. For example, by requiring all “drafts” of competition-related deal documents to be produced (including from the head of the deal team), the rules significantly expand the scope of documents to be produced. The FTC states that obtaining drafts is necessary, given that deliberative documents are “sanitized” by the time drafts become final versions. But such a suggestion misses the point that the final versions of documents instead reflect the considered judgment of those involved in reaching the ultimate determination rather than preliminary thoughts that lack solid analytical value but make for good sound-bites in government complaints. Under the proposed rules, individuals involved in preliminary deliberations are likely to self-censor for fear of creating documents that will be attached to the initial HSR.

CONCLUSION

The unequivocal result of the proposed rules will be increased burden. Even simple no-issues transactions—for example, transactions involving a private equity acquirer where there are no overlaps between the portfolio of the acquirer and the activities of the target firm—will require a substantial investment in filing preparation and will add extra time to the merger clearance process.

The proposed rules are a first step in the rulemaking process. We will provide additional Legal Updates as the process advances.

1 The proposed rules are published at 68 Fed. Reg. 42178 (June 29, 2023).

2 The public has 60 days to comment on the proposal. The FTC then will review the comments and—at its discretion—make any changes that it believes are warranted. Once the FTC issues the final rules, they will take effect subject to a short notice period. Litigation or congressional action to challenge the rules may follow but would not necessarily delay their implementation.

3 FTC, Press Release (June 27, 2023), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/06/ftc-doj-propose-changes-hsr-form-more-effective-efficient-merger-review

4 Statement of Chair Lina M. Khan Joined by Commissioners Slaughter and Bedoya Regarding Proposed Amendments to the Premerger Notification Form and the Hart-Scott-Rodino Rules (June 27, 2023) [“Statement”], https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/cases-proceedings/public-statements/statement-chair-lina-m-khan-joined-commissioners-slaughter-bedoya-regarding-proposed-amendments

5 The FTC has a model voluntary request letter stating the types of information that it would like produced during the initial waiting period. See https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/premerger-notification-program/hsr-resources/guidance-voluntary-submission-documents.

6 Available at https://www.ftc.gov/policy/reports/annual-competition-reports.

7 “Clearance” is the internal process the Agencies use to determine which Agency (the FTC or the Antitrust Division) will conduct any inquiry into a particular deal. An Agency only seeks clearance when it is interested in a transaction, as the vast number of HSRs do not raise meaningful issues. See generally, Antitrust Division Manual (legacy) at III-35 (describing the use of the “no-interest” memorandum for filings raising no competition issues versus the use of the clearance process for deals that require Agency attention), available at https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2015/05/13/chapter3.pdf.

8 FTC & DOJ, “Annual Competition Report FY 2021” at Exh. A, Table 1 (“Data Profiling Hart-Scott-Rodino Premerger Notification Filings and Enforcement Interests”), available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/p110014fy2021hsrannualreport.pdf.

10 The information required for a European Commission filing is set out in Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/914 of 20 April 2023 Implementing Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 802/2004, available at available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023R0914&qid=1688034412362 (Commission Implementing Regulation – Control of Concentrations).

11 Jurisdictions that include public interest considerations as part of their legal test include China, sub-Saharan African countries and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

12 The proposed rules would require parties filing on a letter of intent to “submit a draft agreement or term sheet that describes with sufficient detail the scope of the entire transaction” and to confirm that such transaction “is more than hypothetical.”